How we're Getting There.

It's 7am, and I'm in the middle of two construction sites and a lot of graffiti waiting to get on a Metro Bike with Tiffany Chao and Thomas Szelazek. Unlike the many people who feel helpless yelling, "why would someone build this!", when they are stuck in traffic on a poorly designed street or lost because of a confusing transit system; these two are the people who usually know why or how it happened. Thomas and Tiffany are what they call transportation consultants in the world of urban planning. They make a living studying and improving this city, spending days in meetings, at computers, and on location throughout the city, and state, trying to figure out how to improve mobility for the masses and untangle the knots built by previous generations. As we begin our trip from the Downtown Arts District to their office in Old Town Pasadena they have a lot to say about how we are getting there.

“I didn’t need it. I was paying between $600 - $700 a month with insurance, gas and parking.”

One of the many construction sites in the ever-expanding Arts District.

Prior to relocating to the Arts District, both Tiffany and Thomas were of the many Angelenos who lived by the seat of their cars. For sixteen years, Tiffany lived in LA with her car on the Westside, while Thomas resided near USC before the Expo Line or immediate ride share. Five years ago the couple moved themselves to the Arts District near 7th and Santa Fe – an area known for it's coffee shops and restaurants and the warehouses that house them. This move was their first big attempt to make for a life less dictated by traffic. Their next step was getting down to one car, a goal they accomplished two years ago when Tiffany sold her car saying, "I didn't need it. I was paying between $600 - $700 a month with insurance, gas and parking." Now, with a single car they are commuting to work together which takes about thirty-three minutes door to door.

To unlock a MetroBike you register your tap card and then simply place it on the reader to unlock the bike.

When possible, they would try mass transit, but due to the strenuous twenty-eight minute walk to the Gold Line at the Little Tokyo/Arts District Station, the commute didn't feel totally worth it. Fortunately, just over a year ago that trip was condensed with the introduction of Metro's new bikeshare system, Metro Bike, which added a bike station within three blocks of their home. At $20 a month, unlimited 30 minute rides, it is best designed for frequent riders, casual rides are $3.50 for 30 minutes or $1.75 for 30 minutes with a yearly payment of $40. Despite a semi-confusing price structure, this gave Thomas and Tiffany more mobility. That mobility made for a new goal: commuting to work via Metro once a week. Now at 63 minutes on average, the commute is still longer, but it is doable.

Tiffany can use the front pouch for her bag.

“...the light, which is controlled by circular sensors that detect cars and didn’t turn green for us twice, therefore adding a two minute delay. ”

As we started biking from one end of the Arts District to the other it really hits me how bikeshare has changed this neighborhood. There are few bus routes and none that run north-south and the low-rise steel and concrete buildings coupled with few trees offering shade make for an unfriendly pedestrian experience on a hot day. The sidewalk system has yet to be completed at many key streets which is becoming an increasing problem due to a housing and retail boom. Sometimes sidewalks disappear or streets lack easy pedestrian crossings. The Metro Bikes allowed us to move through the neighborhood more easily. The biggest hold up was at 4th and Molino because of sensors that didn't read us at the light, which is controlled by circular sensors that detect cars and didn't turn green for us twice, therefore adding a two minute delay.

The circle sensors could not tell we needed a green light.

Stopped at this infuriatingly long light, I ask Thomas and Tiffany what they think about the changes. They agree Metro Bike's have increased their mobility but also state that the Arts District has a long way to go to be a neighborhood easily accessed by transit. Tiffany says, "It's about making it easy...proper sidewalks, bike lanes or two main bike routes, there are a lot of curves that make it hard for a driver to see a pedestrian. I often see, including myself, people running across Santa Fe trying to avoid getting hit by one of the five trucks barreling down. People want to walk and bike but the city doesn't always make it easy for them to do it."

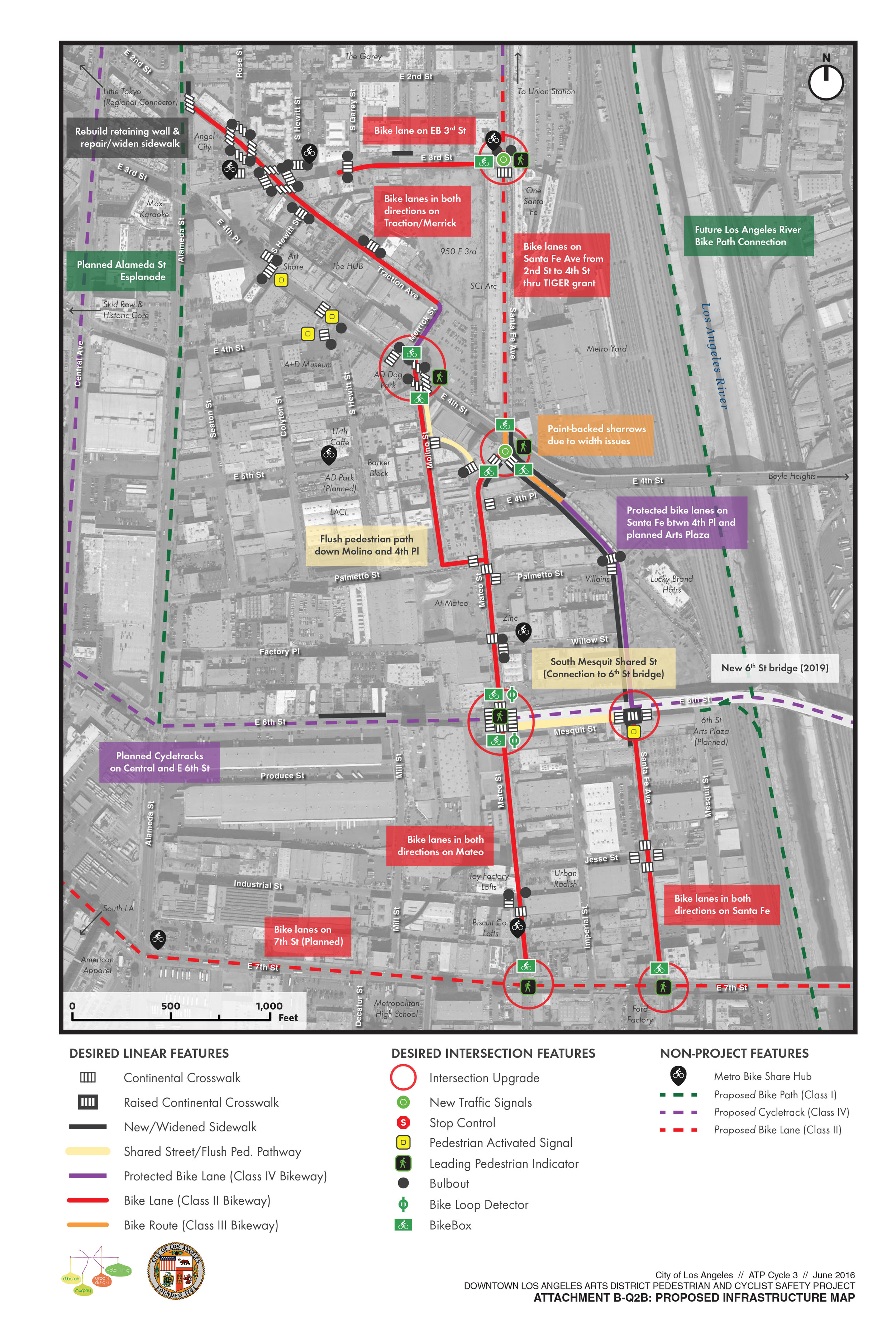

Plan for Pedestrian Improvements in the Arts District

Luckily, the city has recently awarded more than fourteen million dollars to improve pedestrian connections and it can not come soon enough. There are at least twenty retail and pedestrian development projects in the pipeline to date. They acknowledge there may be pushback with changes to street design, Tiffany adds "There's a perception all these planners want people to stop driving. No, we don't want you to stop driving, but maybe you can do something different once a week. There is a woman who was quoted in LA Times recently, she was complaining she couldn't drive from her home at Venice pier to Abbot Kinney because of tourism, but maybe she could have walked."

One or the many missing links for pedestrians in the Arts District. The sidewalk disappears going south on Santa Fe with no crossing to Mateo in sight.

Exactly 10 minutes later we park our Metro Bikes outside of Angel City Brewery, and are walking a block toward the Gold Line to Pasadena. Thomas talks about how critical it is to give people these links to the transit system and that we need far more linkages to give people a reliable way to access the system. Tiffany agreed but added, "it's certainly getting better with all the investment going in, but all these cities in LA county are still providing parking...I think we can grow this system as much as we want, I don't see it getting to it's full potential until we address parking policy." She cites the irony of when city officials and transit planners arrive to a Metro meeting via private vehicles to discuss how to improve the system.

Little Tokyo/Arts District Station

“...I think we can grow this system as much as we want, I don’t see it getting to it’s full potential until we address parking policy.”

Given they both have free parking at work, I ask them why they are experimenting with transit when driving is quicker. Tiffany admits that despite the official status of the car being quicker to work, more variables exist when considering public transit. She often has more to do than just go from home to work and back, and that's when public transit really comes in hand. Quite often she has meetings in the heart of downtown, where parking can be a nightmare, but the gold line is a straight shot making it easier to stop in for a meeting. She also says, "coupled with the bike ride, it gets her moving after sitting at a computer all day. It comes down to an improved quality of life for her." She remarks how it compares to her life on the Westside, "It greatly improved my quality of life. It felt like the equivalent of a $20,000 raise in terms of how my mood changed, and then after getting rid of my car I feel, well 99% of the time, I feel free." She talked about how isolated she felt when her life was controlled by a car. She didn't have exposure to different cultural centers and populations, even finding her new lifestyle has lead to an increase in exposure to different types of food; the Westside was a bubble for her. Thomas adds, "I don't think (public transit) disturbs anything. If anything it makes me walk more and be more active. Maybe I get to work a few minutes later, but heres the thing about people driving alone, I think they real overemphasize the convenience of it." They both joke how easily we forget that when people drive so they can stop and get a coffee on the way to work, often the time spent circling for parking negates the time saved by driving.

On our way to Pasadena.

“...but it’s really about control. If you get into a delay on Metro you will blame Metro, but if you hit traffic you still feel in control”

Thomas and Tiffany don't always have the ability to take public transit, but their rate of use increases as connections become easier and Thomas adds that it isn't just the cities' responsibility to create infrastructure. "We actually survey a lot of companies and the core reasons we get for people not using shared transit is convenience and reliability, but it's really about control. If you get into a delay on Metro you will blame Metro, but if you hit traffic you still feel in control," Thomas says. As transportation consultants they cite the need for companies to embrace more options for their employees to take transit and provide less parking, such as with the B-Tap program at Ace Hotel I discussed last week.

Passing through City Hall in Pasadena.

Thirty-three minutes later we get off at Memorial Station in Old Town Pasadena, and take the final ten minute walk to the office. As we walk through City Hall we pass more Metro Bike stations as the program has now expanded to Pasadena. Thomas remarks, "I hate driving. There is a level of arrogance and security that I get from driving in my car. I think people like that comfort. If you close your windows you are in a literal bubble."

It speaks to some of the irony of Californian environmentalism. We have managed to become an extremely environmentally and socially conscious state that simultaneously embrace a symbol of both environmental abuses and social seclusion. The car allows us to forget we are a society. Something they take transit to remember. "I want to be around my fellow Angeleno," Tiffany says. We all wish to change society on a macro level but are of often unwilling to integrate our lives into that change when it comes to transportation. An example of our inability to modify behavior is occurring at California's beloved national park Yosemite. A recent explosion in popularity has driven up traffic to more than five million vehicles a year. Proposals to have visitors shuttle in to the fairly compact walkable heart of Yosemite, which has been successful in nearby states with National Parks, have been shot down due to lack of interest. Our need for an easy experience can run the risk of destroying what we are trying to experience if we aren't careful.

Pasadena City Hall.

As we walk up to their office I ask them how they are getting home. Tiffany smiles and says, "we're gonna take the train home and go eat in Little Tokyo because we don't have to drive. If we were driving I'd say lets just go home, I don't want to have to deal with and pay for parking.

Transit instructions provided by Citymapper